In the spirit of the EST/Sloan Project’s commitment to “challenge and broaden the public’s understanding of science and technology and their impact in our lives,” we offer this essay on some of the scientific and historical background to BEHIND THE SHEET by Charly Evon Simpson, the 2019 EST/Sloan mainstage production. BEHIND THE SHEET begins previews on January 9 and runs through March 10. You can purchase tickets here.

Background essay by Rich Kelley

The first Women’s Hospital in America is thought to be the four-story, 20-bed institution that used to stand at Madison Avenue and 29th Street in New York City, founded by Dr. J. Marion Sims in 1855 where he operated on ailing white women. That claim, however, ignores the two-story, eight-bed “sick house” Sims had set up on a small slave farm in Mount Meigs, Alabama, where from 1844 through 1849 he performed surgical experiments on between 10 and 17 enslaved women, most of them suffering from what we now call obstetric fistulas.

Dr. Sims had come to Alabama in 1840, at the age of 27, to open a new medical practice. He had closed his first practice in South Carolina after his first two patients, infants, had died, probably from cholera. Sims quickly developed a reputation as a skilled surgeon. In those days bleeding to death was a constant danger during surgery and Sims describes in his memoirs how he relied on speed in the surgical area to save his patients.

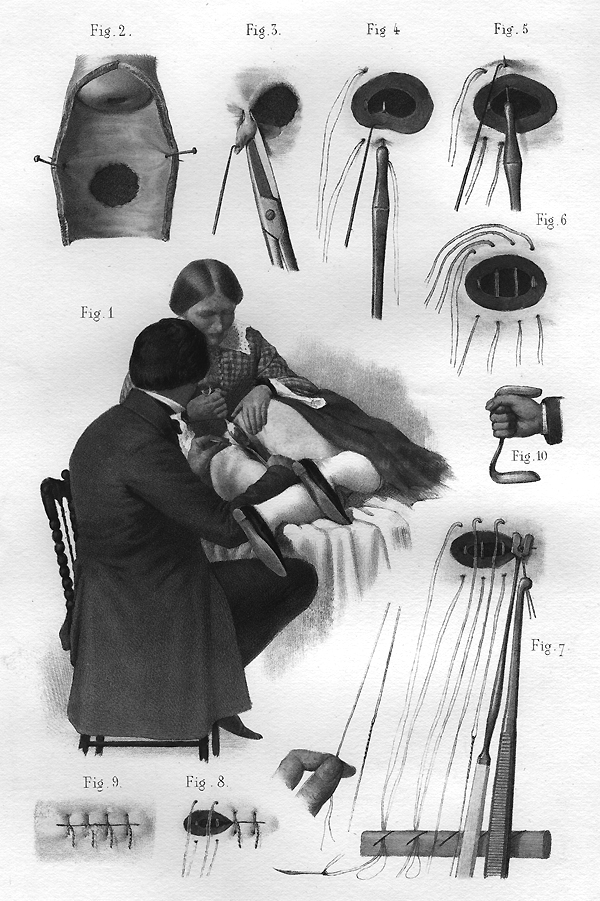

While widely known as the “Father of Modern Gynecology,” Dr. J. Marion Sims was quite frank in his memoirs about his initial distaste for the field: “If there was anything I hated, it was investigating the organs of the female pelvis.” Little was known of female anatomy at the time and, frustrated by what he couldn’t see in 1845 during his first case of an obstetric fistula, Sims turned a pewter spoon into a kind of duck-billed retractor. Describing the first use of the “Sims speculum,” he wrote, “I saw everything as no man had ever seen before. The fistula was as plain as the nose on a man’s face.”

What he saw led Sims to believe he could find a way to repair a devastating condition that had plagued women for centuries. “I said at once, ‘Why cannot these things be cured?’” The case at hand involved the pregnancy of Anarcha, a seventeen-year-old slave girl who had been in labor for three days when Sims was called. He was not able to save the baby, and, days later, he observed that she had developed both kinds of obstetric fistulas: a vesico-vaginal fistula and a rectal-vaginal fistula. These can occur during long, obstructed labors when the infant’s head is too large to pass through the pelvic canal. The infant’s head traps the soft tissues of the pelvis up against the pelvic bone, cutting off the blood supply. When labor continues for several days, the tissues die. In a vesico-vaginal fistula, the wall between the bladder and the vagina breaks down and creates a hole, leading to uncontrollable urine leakage. In a rectal-vaginal fistula, the wall between the rectum and the vagina breaks, causing fecal leakage. The ensuing incontinence often produces infections, strong odors, and, over time, the painful inflammation and scarring of the inner legs. Fistula patients quite often become ostracized from family and friends, depressed recluses, unable to live in their homes.

To test his idea, Sims needed more patients with the same condition. We know from his records the names of two others, Betsey and Lucy. As Sims writes, “I made this proposition to the owners of the negroes: If you will give me Anarcha and Betsey for experiment, I agree to perform no experiment or operation on either of them to endanger their lives, and will not charge a cent for keeping them, but you must pay their taxes and clothe them.”

He kept them for five years. Each had a fistula and was experimented on several times, Anarcha perhaps as many as thirty times. When two years passed without a breakthrough, the white colleagues who had assisted Sims drifted away and he had to train his slaves to assist him in the experiments, including restraining patients during surgery, which was performed without anesthetic. Many became addicted to the opium he gave them to ease their pain.

By continually operating on these women, Sims perfected many of his techniques. To improve his ability to visualize the fistula, he invented the “Sims position,” when the patient lies on her left side with her left leg straight but flexing her right knee and hip, pulling the right leg up.

Sims eventually realized he needed something stronger to hold the repair. On June 21, 1849, he used fine silver wire on Anarcha for the first time. On day seven after the operation he re-examined her and found that the fistula had healed perfectly. Sims was ebullient: “I realized that in fact at last my efforts had been blessed with success and that I had made perhaps one of the most important discoveries of the age for the relief of suffering humanity.”

Sims would go on to a storied career as a surgeon in New York and Europe, but questions continue to rage about his contention that his patients consented to his experiments. Sims defenders make the case that these women had much to gain from these operations given the crippling effects of fistula and that no other treatment existed.

In Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, historian Deirdre Cooper Owens presses the case that we understand Sims in his historical context:

“Gynecological surgeons during the early and mid-nineteenth century were neither exceptionally cruel nor sadistic physicians who enjoyed butchering black women’s bodies, as some scholars have argued. They were elite white men who lived in an era when scientific racism flourished. Ideas about black inferiority were established and widely believed, as was the underlying assumption about black people’s intelligence. Black women, particularly those who were enslaved, were a vulnerable population that doctors used because of easy accessibility to their bodies. Further, the value of black women’s reproductive labor demanded that it be “fixed” when it was seen as “broken” by those who depended on their labor.”

Many question why Sims did not use any anesthetic in his operations on slave women but later did so in New York when his clientele were mostly white women. Some contend that Sims believed that African American women had a higher tolerance for pain. Additionally, when he began his experiments in the 1840s, Sims may not have had full knowledge of what anesthetics were available. The first public lectures about nitrous oxide and diethyl ether did not take place until 1845 in Boston and their use did not become common in surgical practice until the 1850s. But even in the 1850s, Sims remained skeptical about the use of anesthesia. In a lecture to The New York Academy of Medicine in 1857, Sims remarked that the Sims position “permits the use of anesthetics if desired, but I never resort to them in these operations, because they are not painful enough to justify the trouble. “

Owens’ book presents an even-handed account, but importantly, much of the book turns our attention and appreciation to the unheralded experiences and contributions of the women Sims and others experimented on:

“Beginning with those nearly ten black bondwomen who labored under Sims as leased chattel, patients, and nurses, they serve as the counter to Sims’s designation as ’father’. They are the rightful ‘mothers’ of this branch of medicine. . . . Their bodies enabled the research that yielded the data for white doctors to write medical articles about gynecological illnesses, pharmacology, treatment, and cures.”

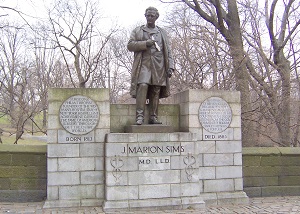

The statue

Sims was the first medical professional to have a statue in his honor in New York City in 1894. It was first in Bryant Park and then moved to Central Park where it stood outside the New York Academy of Medicine on Fifth Avenue. In response to protests about the statue during the summer of 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio charged the Public Design Commission with determining what should be done. In its January 2018 report, the commission was quite scathing in its recommendation that the statue be moved.

“In short, especially in its current location, the Sims monument has come to represent a legacy of oppressive and abusive practice on bodies that were seen as subjugated, subordinate, and exploitable in service to his fame. To confront this legacy in accordance with the principle of Historical Understanding, the Commission feels that the City must take significant action to reframe the narrative presented in the monument.” The status has been relocated to Greenwood Cemetery, where Sims is buried, and there are plans to add in both locations a plaque adding the names of Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey along with a description of the roles they played in Sims’s life.

The state of obstetric fistulas today

In the developed world, ready access to obstetrical care, and especially caesarean section, have virtually eliminated the problem. However, fistulas remain an urgent problem in the developing world. The World Health Organization reports that more than two million young women live with obstetric fistulas in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa and 50,000 to 100,000 new cases occur each year. When those afflicted are able to get timely access to quality obstetrical care, 80% to 95% of them can be repaired surgically.

BEHIND THE SHEET by Charly Evon Simpson, the 2019 EST/Sloan mainstage production, begins previews on January 9 and runs through March 10. Tickets are available here.

Recommended Reading

Books

Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present by Harriet A. Washington (Doubleday, 2007)

Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology by Deirdre Cooper Owens (University of Georgia Press, 2017) Note: the opening to this essay was inspired by the opening of the introduction to Medical Bondage

The Story of My Life by J. Marion Sims (D. Appleton & Co., 1884)

Journal Articles

“The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: A fresh look at the historical record” by Lewis Wall in Journal of Medical Ethics, June 2006.

“J. Marion Sims, the Father of Gynecology: Hero or Villain?” by Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD in Southern Medical Journal, May 2004.

“A History of Obstetric Vesicovaginal Fistula” by Robert F. Zacharin in Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery, June 2008.

“On the Treatment of Vesico-Vaginal Fistula” by J. Marion Sims in The American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1852. Reprinted in International Urogynecology Journal, 1998.

“The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology’, Dr J Marion Sims” by Durrenda Ojanuga in Journal of Medical Ethics, March 1993.

Radio shows/Podcasts

“Remembering Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey: The Mothers of Modern Gynecology” on an episode of NPR’s Hidden Brain, February 7, 2017

“The Controversial Figure of J. Marion Sims” Episode 51 of Legends of Surgery

Websites

J. Marion Sims in the online Encyclopedia of Alabama

J. Marion Sims in Wikipedia

A Dr. J. Marion Sims Dossier at the University of Illinois – poets on J. Marion Sims