The New York Off Broadway premiere of the 2026 EST/Sloan Project production, THE RESERVOIR, written by Jake Brasch and directed by Shelley Butler, a co-production of the Atlantic Theater Company, the Ensemble Studio Theatre and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, begins previews on February 5 at the Linda Gross Theater and runs through March 15. You can purchase tickets here.

This 2025/2026 season marks the twenty-sixth anniversary of the EST/Sloan Project, the joint initiative between the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Ensemble Studio Theatre, “designed to stimulate artists to create credible and compelling work exploring the worlds of science and technology and to challenge the existing stereotypes of scientists and engineers in the popular imagination.” In that spirit, we offer this background essay on Alzheimer’s research by Michael A. Yassa, professor of neurobiology and behavior at the University of California, Irvine, and director of the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

Remembering the Complexity of Alzheimer’s Disease

By Michael A. Yassa, Ph.D.

Memory is the sum of who we are. It is the bridge to our past and our future. It takes a fleeting moment in our consciousness and stretches it out over a lifetime. By the time you finish reading this sentence, the beginning of it has already become a memory. When this process works well, the brain can learn from experience, anticipate what may come next, and make decisions informed by what it has encountered before. Much of what feels stable in our lives depends on this quiet continuity, the ability to carry experience forward without noticing the work it takes.

I have to admit I’m a little biased in my infatuation, since memory is the topic of my research. But memory also matters for another, much more important reason. It is one of the most complex problems the brain has to solve. Creating lasting records of experience and using them later, often under very different conditions, requires coordination across many brain systems. Understanding how memory works turns out to be nearly as difficult as making it work at all.

“When memory begins to fail, the consequences are immediate and deeply personal”

When memory begins to fail, the consequences are immediate and deeply personal. In Alzheimer’s disease, this failure often shows up as the gradual loss of the very memories that anchor identity, relationships, and a sense of continuity in one’s own life. Memory loss is often the earliest and most recognizable sign, either to the person or to their loved ones, that something is wrong. To understand why this happens, it helps to be clear about what memory depends on in the first place.

At a biological level, memory depends on the brain’s capacity to change with experience. We refer to this capacity as learning or plasticity. Learning reflects change as it occurs within neural circuits. Memory reflects what remains once those changes have stabilized, sometimes imperfectly. Importantly, plasticity is not confined to a single system or region. Circuits involved in perception, movement, emotion, and decision-making all adjust with experience. These same mechanisms support the development of skills and habits, the accumulation of knowledge over time, and recovery after injury, when surviving circuits reorganize to maintain function.

What’s incredible is the enduring capacity we have for doing such heavy lifting. The adult human brain contains roughly 86 billion cells, connected by more than a quadrillion synapses. Despite traditional wisdom, those cells do not simply die off as we get older. What does change with age is how easily new connections are formed and reshaped. The machinery that supports plasticity gets sluggish. When that happens, the brain leans more heavily on circuits it has already built and on strategies shaped by years of experience. That shift is what we mean when we talk about compensation.

“Learning and memory systems don’t simply degrade. They adjust how effort and resources are allocated as demands change.”

Aging looks different when you think about it this way. Learning and memory systems don’t simply degrade. They adjust how effort and resources are allocated as demands change. Representations become more selective, favoring stability and efficiency over constant updating.

Once learning and memory are understood as part of a distributed, adaptive system, differences in cognitive function across people make sense. Brains are shaped not only by genetics, but by a lifetime of experience, lifestyle, health, disease, and environment. Those influences build up slowly. Over time, they shape how neural systems coordinate, compensate, and respond when they’re pushed.

This becomes especially relevant in Alzheimer’s disease. For many years, the condition was framed through a relatively simple biological story that begins with accumulation of protein pathology and ends with memory loss. The problem was not that this account was entirely wrong, but that it was incomplete. By treating Alzheimer’s as a single disease with a single underlying cause, it encouraged the search for a single solution. The repeated failure of these approaches forces us to step back for a moment and reconsider our approach.

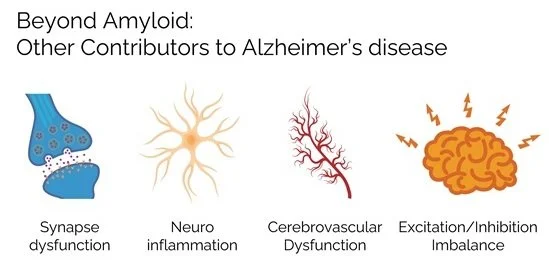

It has now become clear that Alzheimer’s does not unfold through one process at a time. Changes in inflammation, metabolism, blood flow, neural activity, and protein misfolding emerge together and influence one another as time goes on. What matters is how these changes reshape the way brain networks function and how flexible patterns of activity that once supported learning and memory gradually give way to more rigid patterns that are less capable of learning and adapting.

Compensation plays a different role once Alzheimer’s disease enters the picture. Early in the course of the disease, the same adaptive mechanisms that support healthy aging can help maintain memory, even as biological disruption begins. Networks adjust, alternative pathways are used, and function is preserved. For a while, this works. But compensation has limits. As pressures continue to build, the brain’s responses become narrower and less flexible. What once supported adaptation gradually stops working and memory starts to falter. At that point, the system itself has shifted. This is what we mean by failed compensation.

“By the time memory problems are obvious, the brain is often operating under conditions shaped by years of adjustment and reorganization.“

This helps explain why so many treatments have struggled when introduced late. By the time memory problems are obvious, the brain is often operating under conditions shaped by years of adjustment and reorganization. Removing one source of disruption at that stage does not restore earlier patterns of function, because the system has already settled into a different mode.

The same insight has reshaped how the disease is monitored and when intervention is likely to matter. Advances in brain imaging, fluid biomarkers, and physiological measures now allow researchers and clinicians to follow change as it unfolds rather than relying on single snapshots. Timing matters because learning and compensation are still active early on, when brain networks retain more flexibility. At those stages, interventions are better suited to supporting effective compensation and slowing further change than to reversing damage after widespread reorganization has taken hold.

Alzheimer’s disease makes the fragility of memory visible. It shows how much of who we are depends on the ability to hold onto the past and how deeply that ability is woven into relationships, identity, and everyday life. Understanding and addressing this devastating disease requires tools that can track change over time and account for how memory systems respond under pressure. But it also requires accepting that memory is not a single thing that fails all at once. It is a process that adapts, compensates, and eventually struggles under the weight of disruption. Meeting the disease on its own terms means grappling with that complexity to better understand what is being lost, and what can still be preserved.

About the Author

Michael A. Yassa, Ph.D., is a neuroscientist and professor at the University of California, Irvine, where he studies memory, brain aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. His work focuses on how brain systems adapt over time and how disruptions in those systems contribute to cognitive decline.

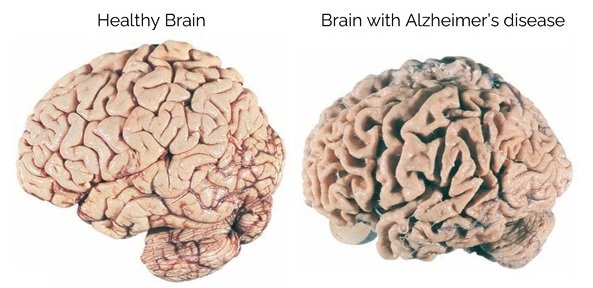

The images in this post are taken from “The Beginning of the End for Alzheimer’s Disease,” an April 2025 lecture by Michael A. Yassa.

THE RESERVOIR begins previews on February 5 and runs through March 15. You can purchase tickets here.