On January 9, 2019, the world premiere of BEHIND THE SHEET, the powerful new drama by Charly Evon Simpson, began previews at the Ensemble Studio Theatre for a run initially scheduled to end on February 3, but extended to February 10 due the entire initial run being sold out a week after its January 17 opening. It has since been extended twice more, to February 17 and then to March 10. Rave reviews greeted its opening, most notably by Ben Brantley in The New York Times who described the play as “a deeply affecting new historical drama” and a “meticulously assembled story of a dark chapter in medical experimentation.” BEHIND THE SHEET is the 2019 Mainstage Production of the EST/Sloan Project, which funded the development of the play and featured it as part of its 2018 First Light Festival.

In this exclusive interview for the EST blog, Charly shares the story of how the play came to be.

(Interview by Rich Kelley)

How did BEHIND THE SHEET come to be? How has it changed through different drafts?

A few years ago, I read an article about a group of women protesting at a statue of J. Marion Sims. As someone interested in how black women’s bodies have been seen and treated throughout history, I found myself trying to learn more about Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy (the three enslaved women we know Sims experimented on) and how slavery intersected with the rise of gynecology. When it came time to apply for an EST/Sloan commission, my brain immediately went back to this history.

The play has changed since the proposal. For example, my first proposal included a more contemporary piece—a black woman gynecologist having to reconcile this history of her field. I soon decided to just focus on the history. Characters have come and gone, scenes have been cut and added, and history has made its way in and out of the story. My first draft was very true to what we know happened. The draft for last year’s First Light Festival allowed a little more room for my voice and imagination, while staying true to the basic facts.

Yes, it was just last April in the 2018 First Light Festival that BEHIND THE SHEET had its first public reading. How has the play changed since?

I've lived with the characters for another eight months so I've gotten to know them better. I've gotten to know the play more. I've been pushed further by those helping me strengthen the piece. J. Marion Sims' statue was removed from Central Park. There's been more media attention about black maternal mortality rates that has also brought more attention to the story of Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy. So, in many ways, it feels like a lot has changed on and off the page. That said, there are scenes that have only changed in the slightest of ways and there are scenes that are completely unrecognizable. As we stepped into rehearsals and now into tech and as we began to see the characters and world truly lived in, new themes and complications appeared and continue to appear. I think (I hope) the play has become a little stronger and a little clearer.

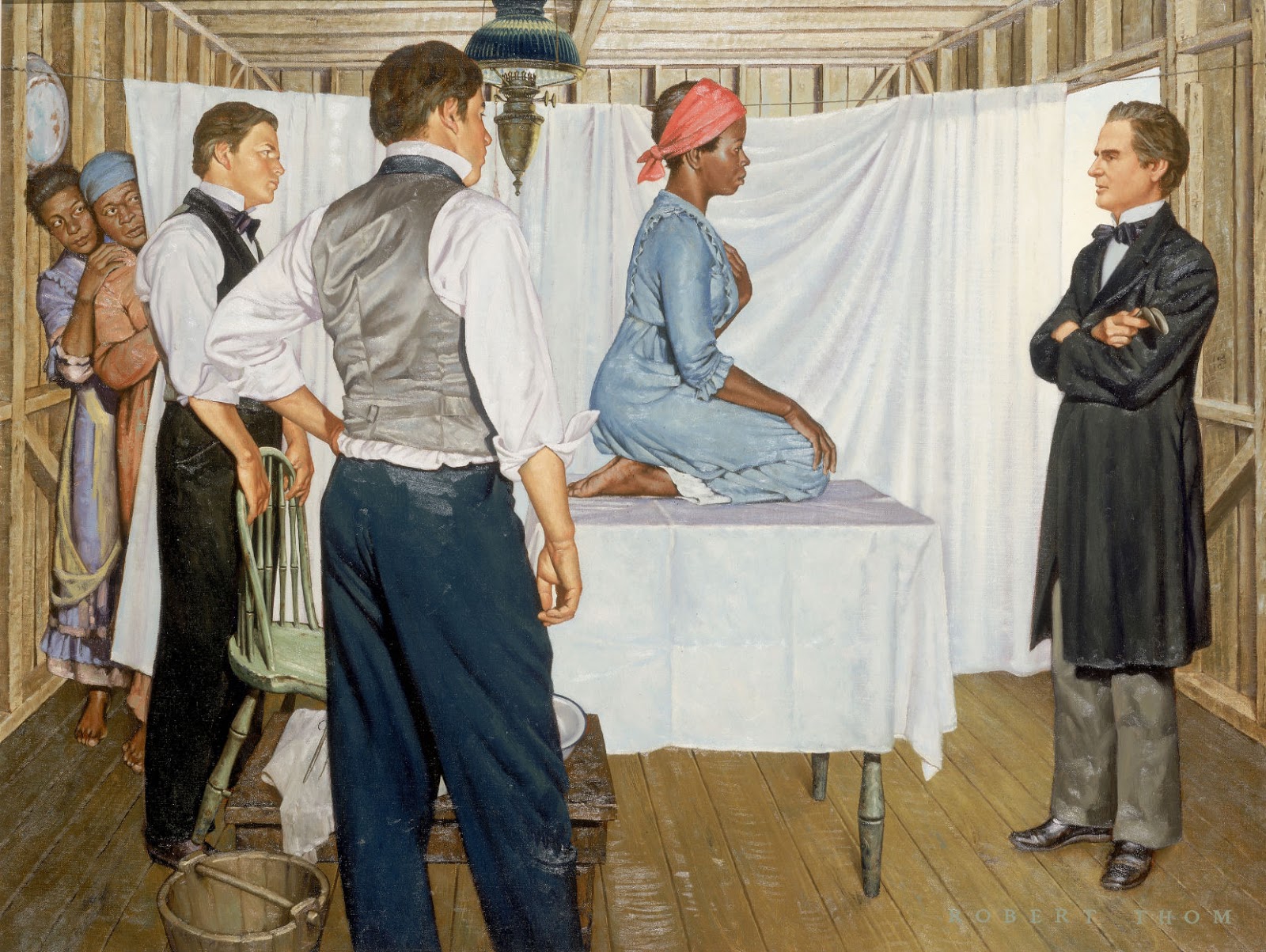

As you say, the play tells a story strongly inspired by the work of J. Marion Sims, a physician often referred to as the "father of gynecology" who practiced medicine in Alabama in the 1840s. He is credited with inventing the speculum and, most notoriously, trying out new gynecological surgical procedures on slaves without using anesthesia. But you don't use his name for your main character, who you call George, and you give the female characters names different from the ones we know from history. Why the name changes? How is the story in the play different from Sims’?

I’ve gone back and forth on the name changes. And, you never know, perhaps the name changes won’t exist in a future draft, but for right now, it allows me some distance from the real story. It allows me to play as a writer in a way that I wasn’t able to when I was using their real names and really focused on getting every historical detail right. With the name changes, I am acknowledging that some of this is fiction. It is historical fiction. I am very aware that we don’t know what Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy were thinking or saying. I have J. Marion Sims’ book, for example, and what he says about them, but I don’t have their words. And I didn’t want to put words in their mouths. I want to shed light on this history and I want to give voice to the experience from the women’s perspective. For me, it is easier to explore the possibility of their perspectives without using their real names. That said, we make a point at the end of the play to bring it back to Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy, and J. Marion Sims. I don’t want to lose them or ignore them. I want the audience to know their names.

Why this play? Why now?

In December 2017, ProPublica published an article entitled “Nothing Protects Black Women from Dying in Pregnancy and Childbirth.” The article is heartbreaking and shows how much more at risk black women are when it comes to pregnancy and childbirth. Education, income…when it comes to black women successfully carrying a child to term and surviving the childbirth and weeks after, it seems nothing is protecting us. In February 2018, Serena Williams shared her own struggles and complications after giving birth. There is a long history of our physical pain being ignored. There is a long history of black women being used for medical innovation while at the same time being ignored by medicine. This history, whether we like to acknowledge it or not, has influenced our current medical systems. And it is important to know the history so that we can make strides away from it.

Women of all races are fighting for their reproductive rights and their healthcare right now, and I think it is important to acknowledge that some women have to fight particular fights that their counterparts do not. This is one of the fights.

What kind of research did you do to write BEHIND THE SHEET?

At first, I didn’t have a consultant. I read J. Marion Sims’ book, The Story of My Life. I read numerous articles, listened to talks (like "Remembering Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey: The Mothers of Modern Gynecology" on NPR) and parts of books like, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present by Harriet A Washington. I read Patient. by Bettina Judd which is a book of poetry intertwining her experience as a patient with the experiences of Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy (as well as other black women who found themselves in the role of patient under racist conditions). I went to talks. Then I had to stop researching and just write the play. I wanted to respect and honor the history, but I also knew I was creating a piece of fiction and so I had to find a balance.

Over the past year, you have been working with a consultant, Evelynn Hammonds, a historian of science at Harvard. What has that process been and how has it informed and changed the play?

Speaking with Evelynn Hammonds was incredibly helpful. Dr. Hammonds highlighted some details about the world/reality of the play that I hadn't gleaned from the books and articles I had read. She turned me on to Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology by Deirdre Cooper Owens, a deeply researched, devastating book I highly recommend. Dr. Hammonds really made clear how different our understanding of surgery is now as compared to then. Doctors weren't in white coats. Keeping tools sterilized wasn't a primary concern. There weren't operating rooms as we think of them. Medicine had a long way to go to resemble what we think of it as. Dr. Hammonds took me through the history of slavery, of using black bodies for medical progress, and the inherent quandary that existed within those. On the one hand, using black people for experimentation was useful because they were human beings and therefore had bodies like those of white people, but on the other hand, the experimentation on black people was considered okay by many due to the fact that black people weren't given humanity in the same way white people were. Dr. Hammonds reminded me that first and foremost Dr. J. Marion Sims, and other doctors of that time period, had a question that needed answering. The play grew in leaps and bounds after my talk with her.

BEHIND THE SHEET features five black slave women and one black slave man. How did you come to decide how many different black slave voices you wanted to dramatize? Did the number or the kind of voices change over time?

To be honest, I’m not sure. It just happened. I started with only three black women, but also wanted to somehow honor the other women Sims experimented on whose names we don’t know. So I felt free to move away from the three women and add the voices that came to me.

There is an article in The Journal of Medical Ethics that states that "Although enslaved African American women certainly represented a ‘vulnerable population’ in the 19th century American South, the evidence suggests that Sims's original patients were willing participants in his

surgical attempts to cure their affliction." What do you make of this statement?

My first instinct is that, sure, if you are in pain and someone offers you a possible way out of that pain, chances are you might be willing to agree to experiments aimed at curing you. That said, “willing” is a…complicated word to use in reference to enslaved people. The power dynamic alone complicates any ideas around the word “willing”. What does willing even mean when your rights have been stripped away and your body is often being used in service of other people? When one does not own your own body, and when your worth is attached to said body, how does consent work? If any of them said “no,” how do we think their owners may have reacted? Also, if there was any notion of willingness and if it was respected at first, was there any room for that “willingness” to end? When Sims took on the financial burden of taking care of these women who were “unfit” to do much of what was expected to them, are we sure he would have been willing to stop? Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy, and the other women—along with J. Marion Sims—didn’t know it would take numerous surgeries to find a cure for fistulas. If Anarcha wanted to stop at surgery 15, would she have been able to? What may have been done to “convince" her to keep going?

We have a tendency to want to make our history seem way more light, bright, and friendly than it actually is. History is complicated. I’d rather we live in the complications than ignore them.

What do you want the audience to take away from BEHIND THE SHEET?

When director Colette Robert first read the play, she said she had to put it down because it made her stomach hurt. I don’t want to cause people pain, but I do hope the audience feels the discomfort, feels the complicatedness, feels the pain that is intertwined in our history. You can be grateful there is a cure for fistulas. You can also be disappointed that it was found at the expense of black women’s bodies. Holding those two feelings inside is possible and it is messy and it is uncomfortable and I want us to do it anyway. I hope the audience walks away feeling that messiness, thinking about that discomfort, and wondering what systems we may have in place that continue this history.

Can you describe the experience of seeing actors embody your characters onstage? They’ve been in your head for years and now, suddenly, they are onstage. What is that like for you?

I can't really describe it. It is like seeing a dream in front of you. I feel so many emotions that I get overloaded and feel nothing...everything and nothing. But then it hits me that this play, my play, is not just mine anymore. It is the cast's, the crew's, the design team's play too. I created the foundation, but they are making it a living, breathing thing. And that's beautiful and I'm so grateful.

You have been a member of EST's Youngblood program. What impact did being a member have on your writing?

I have to say that I think the biggest impact for me was not on my writing, but on my understanding and participation in the theater community. I became a member of Youngblood only two months after moving back to NYC. While I knew a few people from college and high school doing theater in the city, being in Youngblood allowed me to meet a wide variety of actors, directors, writers, stage managers, etc. Many of my first theater opportunities came from people I met at EST. They helped me find my footing and place and continue to even after nearly two years out of the group.

2019 is opening big for you. Beside BEHIND THE SHEET, your play Jump just opened at Playmakers in North Carolina and, also this month, your high school, Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, honored you with a production of Hottentotted. And I believe that as part of its National New Play Network Rolling World Premiere Jump is having three other productions this year: at Milagro in Portland in March, with Shrewd Productions in Austin in May, and at Actor’s Express in Atlanta in June. Big congrats! Is there a story that explains why all this is happening?

Haha. Thank you! Short answer: I have no idea. Longer answer is that I've received a lot of support from old friends, mentors, and teachers and from organizations like the National New Play Network and all that support is coming together this January and the first half of 2019. My family and close friends would remind me that I've worked hard for this and that work is paying off. I'm trying to listen to them. It still hasn't hit me really and I don't know how to process it. This year is going to be like no other and I'm just trying to stay calm and not succumb to my anxiety.

Do you find that your plays inform each other?

Oh yes. I notice that I become obsessed with certain themes and images. And often my plays will show different sides of the themes and images. For example, I'm clearly interested in gynecology right now. BEHIND THE SHEET shows the history of it and my play form of a girl unknown, which I started writing a few months after I started BEHIND THE SHEET, focuses on a 12-year-old black girl around the time she gets her first period. A new play I'm working on came to be after reading articles about how the intersection of racism and sexism is affecting black people. I also have a trio of plays that all have elements of Westerns and the West. Who knows why...but clearly it takes a while for me to work through themes and ideas.

BEHIND THE SHEET started previews on January 9 and runs through March 10. Purchase tickets here.

Portions of this interview appeared previously on this blog when BEHIND THE SHEET had its first reading at the 2018 First Light Festival.

You can hear more from Charly in her interview with Christie Taylor on the January 22 Science Friday podcast.

The schedule for the 2019 First Light Festival has just been published. Reserve your ticket here.