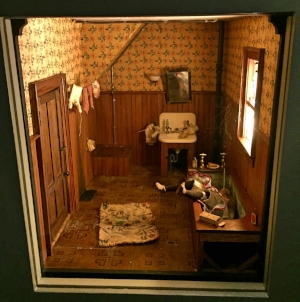

On Thursday, February 8, as part of the 2018 First Light Festival, the EST/Sloan Project will host the first public reading of NUTSHELL, a riveting new play by C. Denby Swanson. The play’s charismatic central character is Frances Glessner Lee (1878-1962), the Chicago heiress often called the “mother of forensic science” because of her lifelong interest in how detectives solve crimes. In 1931, she endowed the first Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University and began hosting seminars and dinners with police detectives. Those interactions with investigators led her to create a unique new forensic learning tool: the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” a series of 19 meticulously-crafted miniature crime scenes. But let’s have our playwright tell us more:

(Interview by Rich Kelley)

How did you come to write NUTSHELL?

In 2015, my friend Elissa Goetschius, a director and dramaturg, posted an article on Facebook about the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.” She lived in Baltimore at the time and had gone to see them at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, where they now reside. Another friend made sure I saw the post, and I was immediately entranced. I knew there was a science play in there. And a play about women’s forgotten history. And a play that invited theatricality.

Frances Glessner Lee is such a larger-than-life character. What kind of research went into the writing of NUTSHELL?

On my trip to Baltimore, Elissa and I spent a couple of days with the Nutshell Studies. Even more importantly, we got to spend time with Bruce Goldfarb, who is in charge of the exhibit at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. He gave us a tremendous amount of background information on Frances, and walked us through the accessible parts of the building. After that, I flew to Chicago to see the Glessner family home, a Chicago landmark and now a museum, and the miniature rooms created by her contemporary, the artist and heiress Narcissa Niblack Thorne, which are on permanent exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago.

There’s no biography yet published about Frances – one is in the works – but I read every piece of writing about her that I could get my hands on – articles, books, blog posts. I watched the wonderful 2012 documentary by Susan Marks, Of Dolls and Murder. I also found books on forensic science, on Chicago architecture, on the medical examiner system, on the privileged social class that Frances was born into. My writing room at home is wallpapered now like a crime investigation with photographs of her, quotes, highlighted text.

In NUTSHELL we experience Lee as she gives a closing lecture to the weeklong seminar she initiated in the forties, the Harvard Associates in Police Science (HAPS), a series of seminars that actually continues today under the auspices of the Chief Medical Examiner in Maryland. How did you decide this was the best way to present Lee theatrically?

Historically, who was invited to speak at these homicide seminars? Detectives. Investigators. Who was not invited to speak? Frances. She was the funder, the hostess. She held the celebratory dinner afterwards, on $8,000 china. It was important to me that the play NUTSHELL be a vehicle for Frances to speak. Her voice was very important to me. I kept thinking of Margaret Edson’s play, Wit, about the John Donne scholar who dies of ovarian cancer, and how her character, Dr. Vivian Bearing, is vibrant, irascible, intensely smart, and emotionally complex. That’s a play that deeply affected me and continues to have a significant influence on my work.

Lee envisioned her miniatures as being useful in teaching detectives how to observe a crime scene. Are the crime scenes Lee’s own concoctions or are they based on actual crimes? Are they meant to be solvable?

Frances created “The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” as training tools for detectives. Her goal was to elevate the profession. She based her scenes on real cases, composites of actual crime scenes. The point of the Nutshells, however, isn’t a solution. Frances intended them as educational tools to train detectives how to look. They can be an infuriating experience – we’re used to Law & Order. Can you imagine what a TV audience’s response would be if every crime show episode, or every season, ended without a definitive answer? The mysteries without that narrative culmination? The point of those shows is to know. Knowing satisfies the audience. The point of the Nutshells is to challenge you to look, to improve the process of investigation. Her goal, she said, was to train investigators to "convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell."

“The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” are not usually available to the public but all 19 were recently on display at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. in the “Murder Is Her Hobby” exhibit (and still viewable online in VR). Have you had the chance to see any of them? What struck you most about seeing them in person?

Because of the funding from the Sloan commission, I was able to make a trip to Baltimore when I first started writing, back in 2016. As I mentioned, I arranged to get access to the Nutshells through Bruce Goldfarb, the special assistant to the Medical Examiner who is in charge of the Nutshells and an expert on them and on Frances. Unfortunately, I was not able to get to the Smithsonian exhibit, but it’s so wonderful that the people’s museum could expand access to this national treasure.

The Nutshells are incredible, weird and obsessive and beautiful and fascinating. After time in their presence, you start seeing the world in a whole new way. There’s a shift in perspective, a shift of scale. They are invocations. They create magic spells. I could have looked at them for weeks and weeks. The important thing for me is that they express the genius of Frances Glessner Lee. In their permanent space at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, framed pictures of her are on the walls, alongside her porcelain bullet wound studies. People are justifiably enamored of the Nutshells, but forget that they came from her, they contain her – she put her own life into them.

The Nutshell studies are painstaking and often grisly miniatures created on a scale of one inch to one foot. Lee hired carpenters to build the sets but hand-stitched the clothing for the dolls herself and produced just two a year for ten years. How do you imagine a production of your play could reproduce them – or their impact – onstage for an audience?

That was the question at the beginning of this writing process. How could a theater audience participate in the Nutshell Studies, which are so small? Theater has the power of words, and it has the power of transformation. So every Shakespeare play starts out with someone saying, “Oh here we are in the city of Verona!” And boom, the audience is in Verona. Frances said – and this is in the play – that to fully experience her “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death”, you just have to imagine yourself six inches tall. So we do. And then the space continues to transform. Frances had a lot of experience in the theater herself. She understood how objects are magical, how space is magical.

The play ends with your introduction of a contemporary crime scene. Why did you choose to end the play that way?

Frances was committed to evidence-based investigation, without the involvement of politics, and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore ferociously continues that commitment. We were talking early on in developing this play, “Why now? Why does Frances, who has been dead for 60 years, speak now?”

During our visit, Bruce Goldfarb took Elissa and me to the room where they set up practice crime scenes. It’s called “The Most Dangerous Room in Baltimore” – because they stage these pretend homicides in there and then use them to train forensic investigators. So it’s a life-size Nutshell Study room. It’s amazing. And I was just like, “Oh my god, Frances is here.” I really felt like she was in the room, in the building. She’s still waiting for truth to lead to justice.

Lee was a rich heiress but most of the Nutshell studies concern the fate of poor, lower class members of society, although always white. Was there a social agenda behind Lee’s creations?

I can’t say what her interest was in social justice issues. But I do think she purposefully made her victims so that investigators would have to pay attention to people they might otherwise overlook. Over 80% of her figures are female. She’s definitely saying something.

University of Maryland criminology professor Thomas Mauriello created six miniature crime dioramas for his students, which he turned into the book The Dollhouse Murders. Visual artist Abigail Goldman sells her miniature “die-o-ramas” online for thousands of dollars. Performance artist Cynthia Van Buhler has used miniature dollhouse scenes to investigate the murder of her grandfather. And Guillermo del Toro, director of the acclaimed The Shape of Water, has optioned Corinne May Botz’s lavish book of photographs, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, for a series of crime dramas for HBO in which a woman investigator uses dollhouse recreations to solve crimes. What do you think is behind this current fascination with dollhouse miniatures as investigative tools?

Oh, I don’t think it’s simply a current fascination. I mean, we’ve been fascinated by miniatures for thousands of years. Pharaohs used miniatures to provide for themselves in the afterlife. Before the advent of photography, door to door salesmen used miniatures to sell furniture. Frances wanted the crime scene miniatures to be small enough that the viewers could see inside a life. Miniatures are like a kind of social autopsy – you get a look at yourself from a new perspective.

Have you written any other plays about science?

In 2002, I was an artist in residence at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School, here in Austin, working with an ensemble of high school students to adapt the ninth grade biology textbook into a play. We collaborated with Doug Rand, a playwright and one of the co-founders of the publishing house Playscripts, who, surprisingly, also has an advanced degree in evolutionary biology from Harvard. (What?! Really. Who knew?) The project resulted in a play called Everything So Far, which the students toured around Central Texas, and which is now published by Playscripts.

I’ve written about Mary Toft, an English woman who gave birth to rabbits. I’ve written about a famous blues club in my hometown of Austin. And I’ve written about my dad, a mathematics professor, and the theory of relativity in my play Relative.

I’m working on a commission of a new full-length play for teens, about vaccines, so that will be my third science play.

What’s next for C. Denby Swanson?

The folks at NYC-based The Drilling Company are producing my play Gabriel: A Polemic, about faith, sisterhood, and free will. Directed by Hamilton Clancy. It opens March 9 and runs through March 26.

I’m also writing a memoir about my first year as a foster parent. I fostered four children over five years and adopted my son in 2014.

The 2018 EST/Sloan First Light Festival runs from February 5 through April 6 and features readings and workshop productions of eight new plays. The festival is made possible through the alliance between The Ensemble Studio Theatre and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, now in its twentieth year.